On December 21, 2024, shortly before 14:00, scientists made the dead speak. ELIZA, the world’s first chatbot, is back. Long simulated but not perfectly reproduced, ELIZA was long considered lost. But in 2021, scientists found an early version of its code in the archives of its creator and spent the years that followed piecing it together.

Coded and iterated between 1964 and 1967, ELIZA was developed by MIT computer scientist Joseph Weizenbaum. Rudimentary by today’s standards, ELIZA was a hit at the time of its creation. He endowed it with the personality of a psychotherapist, and his secretary was so fascinated that she asked Weizenbaum to leave the room when she was chatting with him.

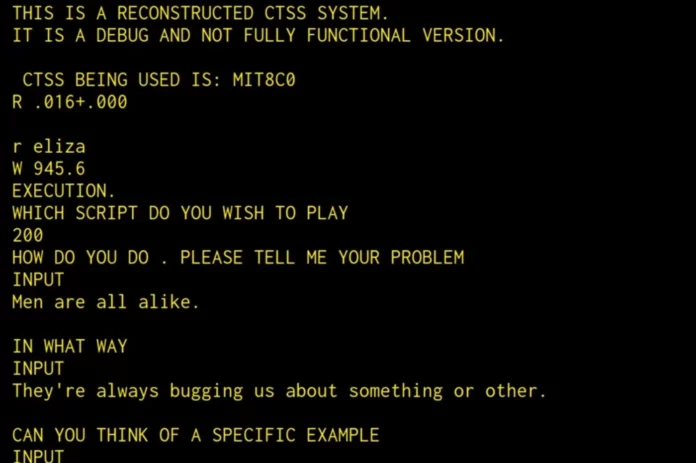

A new scientific article by members of the ELIZA Archeology Project details how they found and resurrected the chatbot, as well as its origins and further spread. Weizenbaum programmed ELIZA in an early language called MAD-SLIP on a computer time-sharing system called the Compatible Time-Sharing System or CTSS.

ELIZA quickly got away from Weizenbaum. As it spread through early computer networks, programmers adapted it to other languages. One of these early clones was created in Lisp by one of the technical leaders of ARPAnet, the precursor to the modern Internet. The Lisp version of Eliza was one of the first bits of data on this nascent network, and it spread rapidly.

“As a result, Cosell’s Lisp ELIZA quickly became the dominant strain, and Weisenbaum’s version of MAD-SLIP, invisible to ARPAnet, was consigned to history,” the article says. “Until it was rediscovered in 2021, the original MAD-SLIP ELIZA was not seen for at least 50 years.”

Ten years later, Creative Computing magazine published a clone of ELIZA written in BASIC. It was 1977, the same year that the Apple II, Commodore Pet, and TRS-80 appeared on the market. These machines led to the explosion of home computers and the spread of the BASIC programming language.

“And it’s likely that a good number of these hobbyists were interested enough in the possibility of AI typing up this BASIC ELIZA (which consisted of only a few pages of code) and experimenting with it themselves,” the scientists say. “Due to its brevity and simplicity, as well as the explosion of personal computers, this ELIZA spawned hundreds of fakes over the decades in every possible programming language, making it possibly the most faked program in history. Just as Cozell’s Lisp ELIZA spread through the ARPANet, BASIC ELIZA spread through the explosive proliferation of personal computers.”

There are now countless versions of this basic ELISA on the Internet, and the original MAD-SLIP version was long considered lost to history. Then Stanford computer scientist Jeff Schrager convinced MIT archivists to dig through boxes of Weizenbaum’s materials, and they made an important discovery: early versions of the MAD-SLIP code.

The code was incomplete, and it took a lot of work and sophisticated emulation to get it running again. “This required numerous steps of cleaning and completing the code, installing and debugging the emulator stack, non-trivial debugging of the found code itself, and even writing some completely new functions that were not in the archives or in the available MAD and SLIP implementations,” the article says.

It took time and a lot of effort, but the code archaeologists got ELIZA working again, and they made it available for everyone to play with. “It’s been tested on various versions of Linux and MacOS, but we’ve noticed some issues with different versions, so your mileage may vary,” the article says. “If it works for you on your computer and you find that you need to change anything, please let us know.”