The music industry’s nightmare came true in 2023, and it sounded a lot like Drake.

“Heart on My Sleeve,” a convincingly fake duet between Drake and The Weeknd, garnered millions of views before anyone could explain who made it or where it came from. The track didn’t just go viral – it shattered the illusion that someone was in control.

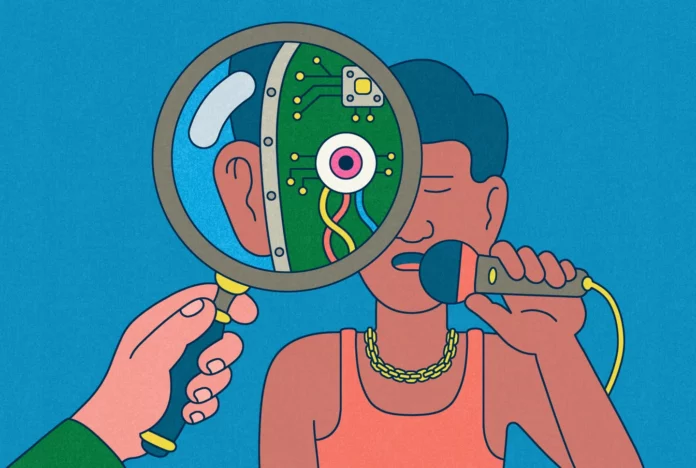

In the pursuit of an answer, a new category of infrastructure is quietly emerging, designed not to stop generative music entirely, but to make it traceable. Detection systems are being built into the entire music pipeline: the tools used to train models, the platforms where songs are uploaded, the databases that license rights, and the algorithms that generate detections. The goal is not just to catch synthetic content after the fact. The challenge is to identify it early, tag it with metadata, and manage its movement through the system.

“If you don’t build these things into the infrastructure, you’re just chasing your tail,” says Matt Adell, co-founder of Musical AI. “You can’t react to every new track or model – it doesn’t scale. You need an infrastructure that works from training to distribution.”

There are now startups that are building detection into licensing workflows. Platforms such as YouTube and Deezer have developed back-end systems to flag synthetic audio at the time of upload and determine how it appears in search results and recommendations. Other music companies, including Audible Magic, Pex, Rightsify, and SoundCloud, are expanding detection, moderation, and attribution functions in everything from training datasets to distribution.

The result is a fragmented but rapidly growing ecosystem of companies that view AI-generated content detection not as an enforcement tool but as an infrastructure for tracking synthetic media.

Instead of detecting AI music after it is distributed, some companies are creating tools to tag it from the moment it is created. Vermillio and Musical AI are developing systems to scan finished tracks for synthetic elements and automatically tag them in metadata.

Vermillio’s TraceID system goes deeper, breaking down songs into their components – such as vocal tone, melodic phrases, and lyrical patterns – and marking specific segments generated by artificial intelligence, allowing rights holders to detect mimicry at the component level, even if a new track borrows only parts of the original work.

The company states that its focus is not on takedowns but on proactive licensing and authenticated release. TraceID is positioned as a replacement for systems such as YouTube’s Content ID, which often misses subtle or partial imitations. Vermillio estimates that authenticated licensing based on tools like TraceID could grow from $75 million in 2023 to $10 billion in 2025. In practice, this means that a rights holder or platform can run a finished track through TraceID to check whether it contains protected elements, and if so, the system will flag it for licensing before release.

Some companies go even further – down to the training data itself. By analyzing what is included in the model, they aim to estimate how many borrowings the generated track has from specific artists or songs. Such attribution could enable more accurate licensing, with royalties based on creative influence rather than post-release disputes. This idea echoes old debates about musical influence – such as the Blurred Lines lawsuit – but applies them to algorithmic generation. The difference is that licensing can take place before the release, rather than through an after-the-fact lawsuit.

Musical AI is also working on a detection system. The company describes its system as multi-level, covering consumption, generation, and distribution. Instead of filtering outbound data, it tracks the origin from start to finish.

“Attribution shouldn’t start when the song is finished – it should start when the model starts learning,” says Sean Power, co-founder of the company. “We’re trying to quantify creative impact, not just catch copies.”

Deezer has developed internal tools to flag fully AI-generated tracks on upload and reduce their visibility in both algorithmic and editorial recommendations, especially when the content looks like spam. Chief innovation officer Aurélien Hérault says that as of April, these tools were identifying approximately 20 percent of new uploads each day as being entirely generated by artificial intelligence, more than double the number in January. The tracks found by the system remain available on the platform, but are not promoted. Ero says Deezer plans to start labeling these tracks directly for users “in a few weeks or a few months.”

“We’re not against artificial intelligence at all,” says Ero. “But a lot of this content is being used in an unfair way – not to create, but to exploit the platform. That’s why we pay so much attention to it.”

Spawning AI’s DNTP (Do Not Train Protocol) pushes detection even earlier – at the dataset level. The opt-out protocol allows artists and rights holders to mark their works as not suitable for model training. While visual artists already have access to similar tools, the audio world is still catching up. There is still no consensus on how to standardize consent, transparency, or licensing at scale. This issue may eventually be addressed through regulation, but for now, the approach remains fragmented. Support from large AI training companies has also been inconsistent, and critics say the protocol will not gain traction unless it is independently regulated and widely adopted.

“An opt-out protocol needs to be non-profit, overseen by several different entities to be trusted,” says Dreihurst. “No one should entrust the future of consent to an opaque, centralized company that could go bankrupt – or much worse.”