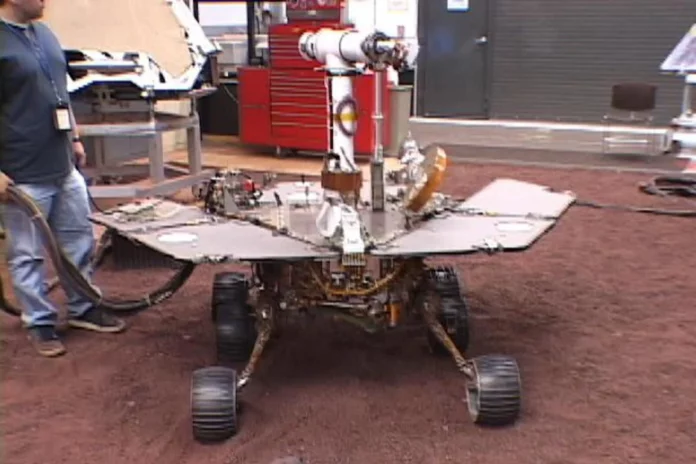

In the spring of 2019, the six-wheeled Spirit rover was reversing to drag the inoperable front right wheel when it got stuck on the sandy Martian surface. Despite months of attempts to retrieve the robot, NASA was unable to free Spirit. Now, engineers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison may have found a way to better prepare NASA robots for work in extraterrestrial environments.

In a paper published in the Journal of Field Robotics, a team of engineers used computer modeling to identify a missing element in the way NASA tests its rovers on Earth. Instead of only considering the effect of gravity on the rover prototypes being tested on Earth, the engineers behind the recent study suggest that NASA has ignored the effect of gravity on the sand itself.

Gravity on Mars is much weaker than on Earth. To account for the difference in gravity between Mars and Earth, NASA engineers are testing lightweight prototype rovers that are about one-sixth the weight of robots sent to the Red Planet. However, recent modeling has shown that Earth’s gravity attracts sand much more strongly than on Mars or the Moon. As a result, the sand on Earth is much stiffer and less likely to shift under the rover’s wheels, while on the Moon it tends to be fluffier.

“We need to consider not only the gravitational pull on the rover, but also the effect of gravity on the sand to get a better picture of how the rover will perform on the Moon,” said Dan Negrut, professor of mechanical engineering at UW-Madison and lead author of the paper.

The study team stumbled upon the missing piece of the puzzle while modeling NASA’s VIPER, or Volatiles Investigating Polar Exploration Rover, which was scheduled to be launched to the moon this year before its mission was canceled. While modeling the VIPER mission, engineers noticed discrepancies between the Earth-based testing of the rover prototype and the physical simulation of the four-wheeled robot on the Moon.

New data suggests that rovers on extraterrestrial surfaces such as the Moon or Mars are more likely to get stuck in sands that are not very easy to handle. Something similar could have happened not only to Spirit, but also to NASA’s Opportunity rover, which spent several weeks in sand in 2005, and Curiosity, which got stuck in soft soil in 2014. By knowing how sand behaves under the lighter gravitational pull of other worlds, NASA can better prepare its robots for the harsh terrain that lies ahead.